This is the first in a series of essays on popular culture and neuroscience. I’m starting with my favourite movie, Blade Runner (1982), and the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) on which it is based, partly because I have been obsessed with both since I was a teenager, but mostly because I can write about both from inside the condition these texts illustrate: autism, and in particular the autistic spectrum disorder still referred to as “Asperger’s syndrome” or “Asperger’s disorder.”

It may sound a surprising claim Blade Runner as an “autistic” film to anyone used to more literal representations of autistism in films like Rain Man (Barry Levinson, 1988) or Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close (Stephen Daldry, 2011) but in many ways Blade Runner is the “Aspie” [1] film par excellence.

Most films about autism are targeted at non-autistics, reflect the non-autistic values and assumptions, and are ultimately and ultimately designed to meet their emotional needs. Many revolve around finding a cure: in Change of Habit (1969), for instance, Elvis Presley, in his last film role, cures an abandoned autistic girl by hugging het close and telling her she has to learn how to love people. Sometimes the direction of cure is reversed: caring for his autistic brother Raymond (Dustin Hoffman) redeems the selfishness of yuppie Charlie Babbitt (Tom Cruise). Either way the autistic experience is framed within the point of view of the non-autistic. But Blade Runner is different; Blade Runner largely dispenses with the non-autistic point of view.

Blade Runner features no characters explicitly identified as having Asperger’s Syndrome; in fact few of them are even human. When Blade Runner was made Asperger’s was barely recognised in the English speaking world (Lorna Wing translated Hans Asperger‘s work in 1981 when the film was already in production). Yet every character, human or otherwise, displays recognizably autistic spectrum (AS) traits – as I will hopefully demonstrate!

The film also reflects the experience of alienation, social exclusion and prejudice common to aspies; what’s more, the film’s intense auditory and visual style and obsessive attention to surface detail mimics the local precedence bias of autistic perceptual processing and induces an effect of sensory overload aspies are familiar with. It features a diagnostic test that bears an uncanny resemblance to tests used in the assessment of autistic spectrum disorders. But most importantly of all, the major theme is one which is of particularly salience to Aspies; the notion that empathy is constitutive of being human, and that a deficit in this often vaguely defined quality is used the marginalise and discriminate against certain groups by denying them humanity (hence the title of this first part).

And to top it all the film features an actress who was herself diagnosed with Asperger’s.

The Autistic Mode

An aspect of autistic thinking I should introduce straight away is associative thinking; making connections between ideas and concepts that are not always immediately obvious to others. In many ways this essay is a demonstration of this mode of thinking as my thoughts on the film serve as a springboard for discussing issues of immediate concern to people with Asperger’s.

The essay is in three parts. “Part 1: Autistic Noir”, attempts to define – briefly – what Asperger’s Syndrome is, and notes some of the traits common to those on the spectrum. I will sketch out the history of the condition as a medical diagnosis and show how definitions have shifted over time. I will look at the obvious – but academically-ignored – intersection of autism, science fiction and fandom, and then focus on the representation of autistic traits throughout the movie. I will also look closely at the psychometric test featured prominently in both the film and the novel, employing discourse analysis as a tool.

In “Part 2: The Neurodivergent Worlds of Philip K Dick” I will look at Dick’s original novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968) in the context of his other work of that period, and follow the evolution of his thoughts on the themes of “flatted affect,” role-taking and empathy, comparing them with current theories proposed by autism specialists like Simon Baron-Cohen and his colleagues.

In “Part 3: The Autistic Mode” I take a linguistic approach to Asperger’s and look at how a preference for metonymy over metaphor makes science fiction so attractive to Aspies; I also look at how postmodernist texts, with their preference for intertextuality over psychological depth, effectively adopt an “autuistic mode” of expression.

These themes in turn trigger wider philosophical discussions on the medicalisation of difference and the intersection of medical, political and legal discourses surrounding autism and other disorders; on “postmodernism” and the “postmodern subject” in film and literature; on the ontological uncertainty about categories of “human” and “non-human”; on the nature of good and evil; on the relationship between the mind and the body; and even on theology. I’ll draw on current neurological research on autism, on the more speculative frameworks of game theory and evolutionary psychology, and on the “principle of continuity” to argue that neurological “norms” should be understood as culturally and historically determined and that a degree of neurological diversity (or “neurodiversity”) is both inevitable and necessary for human beings for much the same reason as biodiversity is to the environment.

Asperger’s Syndrome & The Autistic Spectrum

Asperger’s Syndrome, or “Asperger Disorder”, is a pervasive developmental disorder characterized by significant difficulties in social interaction and emotional reciprocity, and unusually focused or consistent patterns of behavior and interests.

You will usually find these latter traits described in the literature as “restricted and repetitive” rather than “focused or consistent” but I want to avoid using language which defines all Aspie traits in entirely negative terms; for this reason I’ll be referring to ”traits” rather than “symptoms” and I’ll be using the term “neurotypical” (or NT) to denote people not on the spectrum rather than the more loaded term ”normal”.

Autistic traits are on a spectrum of severity and no two autistics are the same; there is a saying in the autistic community – yes, we have a community! – that if you’ve met one autistic, you’ve met one autistic.

I’m going to draw on three kinds of accounts of Asperger’s and other autistic spectrum disorders for this essay: Firstly, on the clinical accounts of specialists in the field such as Hans Asperger himself, Lorna Wing (who first translated Hans Asperger’s work into English), Uta Frith and Simon Baron-Cohen; secondly, on autobiographical accounts of people on the spectrum including Temple Grandin, Daniel Tammet and various Aspie writers and bloggers who’s personal accounts compliment – and sometimes challenge – the theorising of the professionals; and thirdly, on my own experience as a recently assessed Aspie as I learn to adjust to the idea that in certain, significant and specific ways I am ”wired” differently from most other people. Hopefully by presenting these multiple perspectives I can illustrate the range of experiences of people on the spectrum and avoid simplifying or stereotyping

It is important to remember that autistic traits exist on a spectrum and that most of those traits will overlap, to some extent, with those of people who are not autistic. These traits manifest themselves to a different degree in each autistic individual and most people with Asperger’s are capable of functioning independently in society – as are all people with HFA – that’s what “high-functioning” means. Many pass for neurotypical and many will also go undiagnosed.

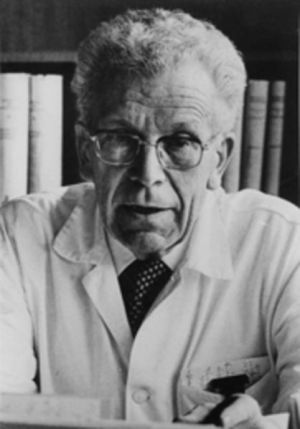

Asperger’s Syndrome was first identified by Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger, director of the University Children’s Clinic in Vienna, in 1944 – the year after another Austrian-born child psychiatrist, Leo Kanner, had independently identified classical autism (or “Kannerian autism”) in the USA; neither was familiar with the other’s work due to the war, and that conflict is the reason why Asperger’s work remained largely unknown outside Germany until the 1980s.

Asperger’s Syndrome was first identified by Austrian pediatrician Hans Asperger, director of the University Children’s Clinic in Vienna, in 1944 – the year after another Austrian-born child psychiatrist, Leo Kanner, had independently identified classical autism (or “Kannerian autism”) in the USA; neither was familiar with the other’s work due to the war, and that conflict is the reason why Asperger’s work remained largely unknown outside Germany until the 1980s.

Asperger did not call the syndrome after himself, of course – doctors do not name conditions after themselves! Asperger called the condition “autistic psychopathy” which makes it sound a lot scarier than it actually is. Asperger was greatly influenced by the work of Eugen Bleuler (who had coined the terms “schizophrenia”, “schizoid”, “autism”) and he regarded the condition as a form of infantile schizophrenia.

For Blueler “autism” was one of the “Four A’s” that characterised schizophrenia: “autism” (social withdrawal; preferring to live in a fantasy world rather than interact with social world); inappropriate or flattened “affect” (emotions in-congruent to the circumstances or situation); “ambivalence” (holding of conflicting attitudes and emotions towards others and self; lack of motivation and depersonalization); and loosening of thoughts and ”associations” (leading to ”word salad,” ”flight of ideas” and ”thought disorder”). To some degree these traits are found in autism but today we would now recognise that autism and schizophrenia are separate conditions, and exist on different spectra – but autism and schizophrenia have historically been conflated and this is reflected in both clinical accounts of the conditions and in literary explorations of autism and schizophrenia such as Martian Time-Slip (1964) by Philip K. Dick.

The term Asperger’s Syndrome was first used in English by the German physician Gerhard Bosch but it was the English psychiatrist Lorna Wing who popularized the term in a 1981 when she translated Asperger’s work; it was also she who classified Asperger’s as part of the autistic spectrum rather than a schizoid personality disorder:

There is no question that Asperger syndrome can be regarded as a form of schizoid personality. The question is whether this grouping is of any value.

—— Lorna Wing, “Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account”

I’ll come back to the early view of Aspergers as a form of schizoid personality disorder later as it is a misunderstanding that lead Philip K Dick to include themes more relevant to people with Aspergers while ostensibly talking about schizoid personalities.

The first English language book on Asperger’s was Uta Frith‘s Autism and Asperger Syndrome published in 1991. (You might have seen Frith presenting Horizon: Living With Autism on BBC2 a few years ago).

Asperger’s differs from other autism spectrum disorders by its relative preservation of linguistic and cognitive development but speech is often atypical and marked by unusual prosody (rhythm, stress and intonation). Speech may be overly-formal, idiosyncratic, tangential or circumstantial, and may include neologisms and metaphors apparently meaningful to the speaker alone; or the AS individual may even display selective mutism.

People with Asperger’s often present with a lack of affect, or emotional display, in terms of facial expressions, hand gestures, tone of voice, laughter or tears; this can give the impression of coldness or aloofness.

Two related traits often found in people with AS are “alexithymia” (the inability to identify and interpret emotional signals in oneself or others) and “mind-blindness” (the inability to predict the beliefs and intentions of others). For some autism specialists such as Simon Baron-Cohen (a former student of Uta Frith) Asperger’s has been characterised as primarily an “empathy disorder”. In their 1985 paper “Does the autistic child have a “theory of mind’?”, Baron-Cohen, Alan M. Leslie and Frith suggested that children with autism do not employ a “theory of mind” and suggest that children with autism have particular difficulties with tasks requiring the child to understand another person’s beliefs:

Our results strongly support the hypothesis that autistic children as a group fail to employ a theory of mind. We wish to explain this failure as an inability to represent mental states. As a result of this the autistic subjects are unable to impute beliefs to others and are thus at a grave disadvantage when having to predict the behaviour of other people.

—— Simon Baron-Cohen, et al, “Does the autistic child have a ‘theory of mind’?” (1985)

I’ll be examining this theory in great detail later as it is this which most directly relates Blade Runner and Asperger’s.

There are, however, traits that the ”mind-blindness” hypothesis cannot easily account for such as the stereotypical behaviour already mentioned and a number of common sensory and motor issues: unusually sensitivity or insensitive to sound, light, and other stimuli; as well as physical clumsiness, problems with proprioception (sensation of body position) and apraxia (motor planning disorder). There are also more alarming features such as somatic self-stimulation (or “stimming”) which can easily be mistaken for self-harm, and ”meltdowns” (which can resemble tantrums or panic attacks). None of these are essential for a diagnosis, however.

It’s a myth that people with Asperger’s are all exceptionally intelligent or have photographic memories or savant abilities: autistic prodigies like Daniel Tammet are the exception rather than the rule. Most people undergoing an Asperger’s assessment will have I.Q. tests, however, if only to rule out other conditions: I had the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS-IV) test which measured my Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), my Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI), my Working Memory Index (WMI) and my Processing Speed Index (PSI). This gave my Full Scale IQ (FSIQ), based on the total combined performance of the VCI, PRI, WMI and PSI, and my General Ability Index (GAI), based only on the six subtests comprising the VCI and PRI. (I’m not telling you my scores.)

AS became a distinct medical diagnosis in 1992 when it was included in the 10th edition of the World Health Organization’s diagnostic manual, International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10); it was added to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) in 1994.

AS became a distinct medical diagnosis in 1992 when it was included in the 10th edition of the World Health Organization’s diagnostic manual, International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10); it was added to the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) in 1994.

Asperger’s was controversially eliminated as a distinct diagnosis in DSM-5 in 2013 and bracketed with autism, High-Functioning Autism (HFA), Pervasive Developmental Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett syndrome under the general category of ”autistic spectrum disorders”.

There is no blood test or brain scan that can diagnose Asperger’s: assessment involves a multidisciplinary team and includes neurological and genetic assessment, as well as tests for cognition, psychomotor function, verbal and nonverbal strengths and weaknesses, style of learning, and skills for independent living. Common tests include the Asperger Syndrome Diagnostic Scale (ASDS), Autism Spectrum Screening Questionnaire (ASSQ), Childhood Asperger Syndrome Test (CAST), Gilliam Asperger’s Disorder Scale (GADS), Krug Asperger’s Disorder Index (KADI), and the Autism Spectrum Quotient. An assessment may also include an IQ test to rule out other conditions and to indicate the best course of action for any therapy. I was diagnosed as an adult. My assessment took 18 weeks.

A number of high profile people have spoken openly about having Asperger’s including electronic music pioneer Gary Numan, who’s stage persona, characterised by affectlessness, distance and awkward posture, make him almost a poster boy for Asperger’s; others include Nobel Laureate Vernon L. Smith, actor Paddy Considine, and Blade Runner actress Daryl Hannah. Others elsewhere on the autistic spectrum include author and autistic savant Daniel Tammet and food animal handling systems designer Temple Grandin, who was subject of the 2010 HBO biopic Temple Grandin starring Claire Danes; I’ll make several references to Numan, Hannah, Tammet and Grandin throughout this essay. [2]

In recent years many aspies have adopted the social model of disability and argue that Asperger’s should be regarded as a different cognitive style rather than a ”disability” as such; from this neurodiversity movement has emerged, with the term neurotypical (abbreviated NT) used to denote those not on the autistic spectrum in preference to the loaded term ”normal”.

So what does all this have to do with a film about a detective who hunts robots? And how did a film made before Asperger’s was officially recognised come to capture the essential characteristics of life on the autistic spectrum?

Anthropologists on Mars

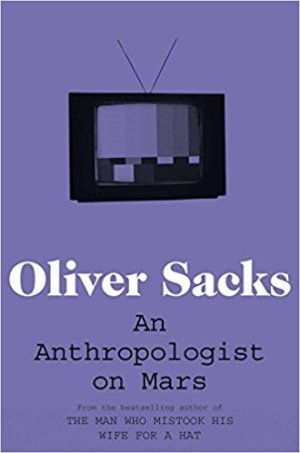

An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales (1995), a collection of essays on neuroscience by Oliver Sacks, takes it’s title from the chapter on Temple Grandin, an autistic woman who is also professor of animal science at Colorado State University, and author of Emergence: Labeled Autistic (1986) and Thinking in Pictures: Other Reports from My Life with Autism (1996):

An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales (1995), a collection of essays on neuroscience by Oliver Sacks, takes it’s title from the chapter on Temple Grandin, an autistic woman who is also professor of animal science at Colorado State University, and author of Emergence: Labeled Autistic (1986) and Thinking in Pictures: Other Reports from My Life with Autism (1996):

What, I wondered as we walked through the horsetails, of Temple’s cosmogony? How did she respond to myths, or to dramas? How much did they carry meaning for her? I asked her about the Greek myths. She said that she had read many of them as a child, and that she thought of Icarus in particular—how he had flown too near the sun and his wings had melted and he had plummeted to his death. “I understand Nemesis and Hubris,” she said. But the loves of the gods, I ascertained, left her unmoved—and puzzled. It was similar with Shakespeare’s plays. She was bewildered, she said, by Romeo and Juliet (“I never knew what they were up to”), and with “Hamlet” she got lost with the back-and-forth of the play. Though she ascribed these problems to “sequencing difficulties,” they seemed to arise from her failure to empathize with the characters, to follow the intricate play of motive and intention. She said that she could understand “simple, strong, universal” emotions but was stumped by more complex emotions and the games people play. “Much of the time,” she said, “I feel like an anthropologist on Mars.”

—– Oliver Sacks (1993) “An Anthropologist on Mars,” The New Yorker, 27th December, 1993

The conceptual metaphor of Martian/Autistic has frequently been used by autistics and their carers to describe their experiences: the largest online Aspie community site, for instance, is called Wrong Planet.

Sf titles like Stranger in a Strange Land (Robert A. Heinlein, 1961) and The Man Who Fell to Earth (Walter Tevis, 1963) will strike a particular cord with people familiar with autism (David Bowie‘s affectless performance in Nicolas Roeg‘s film version of The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) brings out this vulnerable, otherworldly quality even more). Star Trek writer – and tribble creator – David Gerrold called his novelette about his adopted autistic son The Martian Child (1995) and Kathy Lette alludes to Tevis’s novel in the title of her semi-autobiographical novel The Boy Who Fell to Earth (2012) (Lette and her son Julian spoke about his Asperger’s – or “Asparagus Syndrome” – recently on the documentary Horizon: Living With Autism presented by Uta Frith).

In Thinking in Pictures, Temple Grandin wrote that that, as a teenager, she identified with Mr Spock from Star Trek: The Original Series. She also paid tribute the character in an article she wrote to mark actor Leonard Nimoy’s death:

When I was an awkward teenager who did not fit in with the other kids, the logical Mr Spock was a character I could really identify with. At this time, I did not know why I related to Spock because when I was a teenager, I did not know that my thinking process was different from that of most other people. I assumed that my logical picture-based thinking was the way that everybody thought.…

——Many autistic people have identified with Spock; friends and families of autistic people also have gained greater understanding of their friend and relative by comparison to Spock.

—— Temple Grandin, “The effect Mr Spock had on me,” The Conversation, March 9, 2015

Grandin has also said she identified with Data from Star Trek: The Next Generation. Like Spock, Data has a logical, systemizing mind, presents with a marked lack of affect, and generally struggles to comprehend human social behaviour (particularly humour). This points to another popular sf metaphor for autism, and the one which will concern us here: the autistic as android. One of the earliest case-studies of autism was Bruno Bettelheim‘s “Joey: A Mechanical Boy” (Scientific American, 200, March 1959) about an autistic boy who saw himself as a robot. Bettelheim’s psychoanalytical theories about autism – the notorious “refrigerator mother” model – have been entirely discredited but the this case study is just one instance of an autistic person employing the autistic-as-robot metaphor to make sense of his life.

This expropriation of non-autistic texts by autistics and their families is an example of “textual poaching”. The term was first coined by the French scholar Michel de Certeau in The Practice of Everyday Life (1984) and later developed the way fans currently understand it by Henry Jenkins in Textual Poachers: Television Fans and Participatory Culture (1992). Audiences, according to de Certeau and Jenkins, are far from the passive consumers of media they are often characterised as, and are, in fact, active participants in the creation of meaning. Texts – films, books, television programmes, even fashion – are the raw material on which fans work to create material relevant to ourselves. An obvious example is “Slash fiction,” a form of fan fiction in which same sex characters with no apparent sexual interest in each other in the parent texts are pared off: these stories were originally written by heterosexual women but became a focus of interest for the LGBT community almost entirely excluded from the official canon. The first such stories involved James T. Kirk and Mr Spock from Star Trek and other pairings have included Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson (which is ironic as Spock and Holmes have far more autistic traits than homosexual ones.)

The first sf novel to feature an actual autistic character – as opposed to a metaphorical one – was Martian Time-Slip (1964) by Philip K. Dick, author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1966) and a number of other science fiction novels of great interest (I will be looking at several in some depth in “Part Two: The Neurodivergent Worlds of Philip K Dick”).

The first sf novel to feature an actual autistic character – as opposed to a metaphorical one – was Martian Time-Slip (1964) by Philip K. Dick, author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1966) and a number of other science fiction novels of great interest (I will be looking at several in some depth in “Part Two: The Neurodivergent Worlds of Philip K Dick”).

Another autistic boy who can bend reality is Seth in Richard Bachman (aka Stephen King)’s under The Regulators (1996).

More recent novels include Elizabeth Hand’s Winterlong (1990), Mary Doria Russell’s Children of God (1998), William Gibson‘s cyberpunk All Tomorrow’s Parties (1999) and Charles Stross and Cory Doctorow‘s The Rapture of the Nerds (2012); while short stories include Zoran Zivkovic’s “The Whisper” (Interzone #170, August 2001) and Brenda Clough’s “Tiptoe, On a Fence-Post” (Analog #207/208, July-August 2002)

The eponymous Crake, from Margaret Atwood‘s Oryx and Crake (2003) has Asperger’s, and attended the Watson–Crick Institute – nicknamed “Asperger’s U” because it is populated by aspies. Students there refer to non-autistics as “neurotypicals” in a pejorative sense, much in the same way students at Hogwarts refer to non-magicians as “muggles.”

Elizabeth Moon‘s near-future thriller Speed of Dark (2002) features an autistic scientist who’s employers attempt to ”cure” him while Greg Egan’s hard sf novel Distress (1995) includes a subplot concerning the ”Voluntary Autists Association” who actively campaign against the ”curing” of autistics. Both novels take neurodiversity as a major theme.

Elizabeth Moon‘s near-future thriller Speed of Dark (2002) features an autistic scientist who’s employers attempt to ”cure” him while Greg Egan’s hard sf novel Distress (1995) includes a subplot concerning the ”Voluntary Autists Association” who actively campaign against the ”curing” of autistics. Both novels take neurodiversity as a major theme.

Science fiction in other media has featured autistic characters: these include Bob Melnikov (Dmitry Chepovetsky) in ReGenesis (2004-08), who’s Asperger’s was of central concern to the later series, and the Alternative World Astrid Farnsworth (Jasika Nicole) from Fringe (2008-13).

One of the most interesting – and ironic – examples of a character actually diagnosed with Asperger’s by a psychologist onscreen is Cameron (Summer Glau), the cyborg in Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles (2008-2009)! This occurs when she visits an artificial intelligence expert now working as a school psychologist in the episode “The Tower Is Tall but the Fall Is Short” (Season 2, Episode 6).

According to writer Zack Stentz, Cameron was deliberately conceived of with Asperger traits in mind:

Robot and android characters also feel particularly relevant in an age when we’re beginning to realize that not all humans process information and experience the world in the same ways. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that many autistic people (Temple Grandin to name one example) have written about how closely they identify with android characters like Data. There are some very relevant analogies in how some people with autism and Asperger’s syndrome interact with the neurotypical with how an intelligent android tries to understand human behavior from an outsider’s perspective…

——In fact, I sometimes wove some of my autistic daughter’s traits and mannerisms as well as my own (I’ve been told by her therapists that I’m on the Asperger’s spectrum myself) into the writing of some of the robot/AI characters on “The Sarah Connor Chronicles.” It was fun to bring her to the set one day so she could watch a scene being filmed between an artificial intelligence and a little girl. She understood immediately that the dialogue was modeled on a real conversation between her and her brother, and was greatly amused by it.

—— Zack Stentz, “Why we love androids on TV“, Salon, 17th Nov 2013.

A later episode, “Complications” (Season 2, Episode 6), pays homage to Blade Runner‘s Voight-Kampff test when Sarah Connor rescues a tortoise lying on its back by the side of the road.

Of non-sf TV characters with clearly identifiable aspie traits, Dr. Spencer Reid (Matthew Gray Gubler) from Criminal Minds (2005-Present), Maurice Moss from The IT Crowd (2006-2013), Sheldon Cooper (Jim Parsons) from The Big Bang Theory (2007-Present) and Abed Nadir (Danny Pudi) from Community (2009-Present) are all science fiction fans. (Spencer Reid is a fan of Isaac Asimov’s I, Robot (coll., 1950), which features the distinctly aspie-like “robopsychologist” Susan Calvin.)

This reflects a fact about fandom which is widely acknowledged yet under-researched. Autistic fans are over-represented in sf fandom but virtually no academic research has been undertaken on the subject, compared with (comparatively) less marginalised groups; where the connection is addressed it is almost always by people with ASDs themselves (e.g. Will Hadcroft’s The Feeling’s Unmutual: Growing Up with Asperger Syndrome (Undiagnosed) (2004)). Indeed while fandom will police itself for any sign of sexism, racism or homophobia, fans and producers alike will casually toss around disablist terms like ”ming mongs” with impunity. The stereotypical ”fanboy” – socially inept, unfashionably dressed, obsessed with minutia, and almost certainly still living at home with their parents – is drawn entirely from anti-autistic tropes, and is the scapegoat for all that is ”wrong” with fandom.

It was actually through an article in a science fiction magazine that I became aware of Asperger’s when Gary Westfahl‘s article “Homo aspergerus: Evolution Stumbles Forward” first appeared in the sf magazine Locus. Westfahl suggested that science fiction is the ideal vehicle for exploring the sense of alienation experienced by people with Asperger’s:

Looking back at the science fiction of the 1930s pulp magazines, filled with lonely adventurers on solitary quests to distant planets and the far future, one can easily see how these stories would appeal to those young men (and some young women), then regarded only as “reclusive” or “eccentric,” who we would now classify as undiagnosed cases of Asperger’s Syndrome. As I can testify, a person with this condition always feels like an alien being in an alien world: why are all these people able to relax and have fun at this party while I am feeling so uneasy and uncomfortable? Why am I so different from everybody else? Indeed, while one typically believes that people turn to science fiction in search of colorfully unusual vicarious experiences, an entirely different set of motives often may be in play: to a teenager in the 1930s with Asperger’s Syndrome, a story about an astronaut encountering aliens on Mars might have had an air of comforting familiarity, in contrast to stories set in the bizarre, inexplicable, and thoroughly socialized worlds of Andy Hardy and the Bobbsey Twins.

—— Gary Westfahl, “Homo aspergerus: Evolution Stumbles Forward”

Blade Runner, in particular, has many fans on the autistic spectrum and a number have related the films thematic concerns to their own experiences:

Blade Runner is far more succesful at portraying the reality of being autistic both in the time the film depicts and when it was made. Even the shock of being told that you are adopted some time after your eighteenth birthday does not come close. Being told that you were abused without mercy by parental units, teachers, peers, and authority figures because of a difference in the structure of your brain that you can help no more than the colour of your hair, eyes, or skin is like being told that the bad man hurt you because something is wrong with him. Your first point on the agenda is to figure out how you look at the world, and yourself to a degree, again. The second point is “where do we go from here?”. And Blade Runner‘s accuracy in the second point really hits hard. The film stops dead with Deckard getting in the elevator. In the real world that grows more and more like Blade Runner by the day, the film seems to stop dead because there literally is nowhere to go.

—— Dean McIntosh, “Revisiting the classics: A look at Blade Runner” at I Still Find It So Hard

It’s the similarity between the diagnostic tests for Asperger’s and the Voight-Kampff test which has attracted the attention of many Aspies to Blade Runner and to Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

”Are Replicants Aspies?” asks one poster at Wrong Planet:

Recently, I’ve been thinking about the movie Bladerunner, or more specifically, the replicants. It struck me how, as their creator, Tyrel, described them, they only have a few short years to learn how to learn emotional responses that everyone else takes for granted. They sound a great deal like us, except it takes us pretty much a lifetime. Anyone else have an opinion?

Another poster responds:

I d have a similar opinion of the film, I actually saw the thing and the first thing that I wondered was if i’d pass the test used.

An Aspie post at aspergersbutterfly entitled ”Bladerunner, revisited” makes a similar connection:

Close friends of mine will immediately groan at this title, and may very well not even bother to read this post at all. I, in my single-minded, Asperger-ly focused way, bring everything back to Bladerunner like Terry Gross, of NPR’s Fresh Air, somehow manages to brings every conversation, with every guest, back to the HBO show, Oz. But this time, I have found out why this movie has resonated within me so much throughout the years: the empathy test that the replicants must pass. I always found myself siding with the replicant; I too would have asked the same questions, would have been confused by the ambiguity of the questions. I was smart like Roy Batty, crazy like Priss, and had a childish demeanor like that of JT. Am I a replicant? Or were replicants modeled on Aspie’s? Or perhaps its high time I reread the book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

I will return to the V-K test in detail in the next section and I think the relationship between Blade Runner and Asperger’s goes far beyond the parallel between Aspies and replicants but firstly I want to look at some points of interest in the film.

Autistic Noir

Blade Runner (1982) is a science fiction film noir directed by Ridley Scott, loosely adapted from the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). It is widely regarded as both a landmark in postmodern cinema and the definitive cinematic cyberpunk text; it is noted for it’s thematic density and the detail of it’s futuristic mise-en-scene.

Blade Runner (1982) is a science fiction film noir directed by Ridley Scott, loosely adapted from the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? (1968). It is widely regarded as both a landmark in postmodern cinema and the definitive cinematic cyberpunk text; it is noted for it’s thematic density and the detail of it’s futuristic mise-en-scene.

There are various edits of the film but I want focus on two in particular: the “European Theatrical Cut” from 1982, in which form I originally saw the film and which inevitably influenced my subsequent readings of it, and the preferred ”Final Cut” released in 2007. I’ll note minor differences as I go along but for now the major one is that the Theatrical Cut includes a controversial world-weary narration intended to clarify the story for audiences less accustomed to science fiction story-telling – but which tends to hammer home the thematic points a little too heavily.

The film begins with senior Blade Runner Dave Holden (Morgan Paull) about to administer a psychometric test to Leon Kowolsky (Brion James), a new employee at the Tyrell Corporation which manufactures “replicants” (the film’s term for androids); Holden, we later learn, is a senior bounty hunter or “blade runner”, and is following a hunch that a group of escaped replicants might be attempting to infiltrate the company which created them and Leon is a suspect. The psychometric test, or “Voight-Kampff” (sic), measures physiological responses to a series of hypothetical questions involving cruelty to animals in order to measure the subject/suspect’s “empathy” – replicants being presumed to have none. Holden is badly injured when Leon realises he has been unmasked as a replicant and pulls out a gun. (I will look at this sequence in great detail shortly as it is the key to understanding the interest of the movie for many of us with Asperger’s.)

The scene then cuts to the neon-lit, rainswept sweets of down-town Los Angeles where we meet the film’s protagonist and, in the Theatrical Cut, narrator, Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford), a burnt-out and retired blade runner:

DECKARD (VO): They don’t advertise for killers in the newspaper. That was my profession. Ex-cop. Ex-blade runner. Ex-killer

Deckard is all-but arrested by dapper detective Gaff (Edward James Olmos) and taken to a kipple-strewn police station where his former boss, sleazy police chief Harry Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh) blackmails him into completing Holden’s mission.

BRYANT: I need ya, Deck. This is a bad one, the worst yet. I need the old blade runner, I need your magic.

DECKARD: I was quit when I come in here, Bryant, I’m twice as quit now.

BRYANT: Stop right where you are! You know the score, pal. You’re not cop, you’re little people!

DECKARD: No choice, huh?

BRYANT: No choice, pal.

Bryant explains that a group of six replicants, or ”skin-jobs” as he calls them, lead by the charismatic Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer), have made their way to Earth. Two have already been killed while attempting to enter the Tyrell building, but four, Batty, Leon, Pris (Daryl Hannah) and Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) remain at large. (In the Theatrical Cut Bryant says that one was killed entering the building – a continuity error left in when another replicant, Mary, who was supposed to have been injured during the break-in, was written out. The Final Cut corrects the error by having Bryant say that two were killed; nevertheless, the continuity error lead to some interesting speculation about the identity of the sixth replicant which I will come back to later.)

The replicants are a highly sophisticated new model, the Nexus 6, stronger and more intelligent than their creators – but with a built-in limitation:

BRYANT: The Nexus 6 was designed to copy human beings in every way except their emotions. But the makers reckoned that after a few years they might develop their own emotional responses – hate, love, fear, anger, envy. So they built in a fail safe device..

DECKARD: What’s that?.

BRYANT: The Nexus 6 has only four years to live.

As in the novel, the replicants are virtually indistinguishable from human beings and it requires the ”Voight-Kampff” test to identify them. Before Deckard begins his mission he is asked by Eldon Tyrell, creator of the ”Nexus Six” generation of replicants, to demonstrate the test on his assistant Rachael (Sean Young) – a scene which recreates that in the book virtually word for word. The test measures blush responses, pupil dilation, heart rate and other physiological responses to a series of hypothetical questions involving cruelty to animals in order to measure the subject/suspect’s empathy – replicants being presumed to have none. It normally takes 20-30 questions to identify replicants but it takes Deckard over a hundred to determine that Rachael is, unknown to herself, a replicant.

Over the course of the film the distinction between human and replicant becomes increasingly blurred. The replicants are shown to possess feelings for each other: their ice-cool leader, Roy Batty and the ”basic pleasure model” Pris are clearly in love, and Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) is working as a performer in a sleazy sex show to support the others. Deckard, on the other hand, is revealed to be both ruthless and cowardly: he shoots the fleeing Zhora in the back and virtually rapes Rachael who has fallen in love with him. He also shoots the unarmed Pris and attempts to shoot Batty in the back. Despite all this Batty spares Deckard’s life during the grueling climax of the film and Deckard, having finally accepted the humanity of the replicants, flees with the now fugitive Rachael to an uncertain future.

A major difference between the Theatrical Cut and the Final Cut is that the former includes a tacked-on ending where Deckard and Rachael fly off into a lush countryside to live happily ever after having discovered that Rachael doesn’t have a four-year lifespan at all; the Final Cut ends simply with Deckard and Rachael leaving Deckard’s apartment and Deckard discovering an origami unicorn left by Gaff. The Final Cut fixes some technical issues and continuity errors (including the discrepancy in the number of replicants) but more significantly removes the narration and the happy ending and adds a brief dream sequence featuring a unicorn which hints that Deckard himself is a replicant. (There are other differences and I’ll come to them later.)

Blade Runner differs in many details from the novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? – where and when it is set, character names, even minor details like the spelling of ”Voight-Kampff” – but significantly the test remains unchanged. This suggests the writers knew just how important the test is thematically.

The most significant difference between Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and any version of Blade Runner is in the representation of the androids: Dick was considerably less sympathetic to them than Ridley Scott:

“To me, the replicants are deplorable. They are cruel, they are cold, they are heartless. They have no empathy, which is how the Voight-Kampff test catches them out, and don’t care about what happens to other creatures. They are essentially less-than-human entities. Ridley, on the other hand, said he regarded them as supermen who couldn’t fly. He said they were smarter, stronger, and had faster reflexes than humans. ‘Golly!’ That’s all I could think of to reply to that one. I mean, Ridley’s attitude was quite a divergence from my original point of view, since the theme of my book is that Deckard is dehumanized through tracking down the androids. When I mentioned this, Ridley said that he considered it an intellectual idea, and that he was not interested in making an esoteric film.”

—— Philip K. Dick, quoted in Paul Sammon, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner

Scott’s film reverses Dick’s theme: where Dick concerns himself with the ‘dehumanisation” of humans Scott extends the notion of ”human” to the replicants.

Cyberpunk, Postmodernism and the Flattening of Affect

Critics who have made a career out of Missing the Point have drawn attention to the apparent disparity between the richly imagined visual detail of Blade Runner and the ”flatness” of the performances or ”depthlessness” of the characters – as if this is a failure of the film itself rather than the critic’s comprehension.

Flattened affect is actually a theme of the novel, and of the film; a feature, not a bug. Almost the first thing we learn about Deckard in the film is his inability to express his emotions. This is spelt out in his introductory narration in The Theatrical Cut:

DECKARD (VO): Sushi. “Cold Fish.” That’s what my ex-wife used to call me.

Earlier drafts suggest Deckard’s ex-wife and child have emigrated Off World but least in the Theatrical Cut Deckard has had a human relationship: The Final Cut removes even that! The photos that decorate Deckard’s home are clearly decades, if not centuries old; they do not represent emotional ties to people Deckard has known.

All of the characters in Blade Runner and are socially isolated: Eldon Tyrell lives alone in his vast ziggurat except for Rachael, who is a replicant; he is one of three Geppetto characters in Blade Runner. Eye-manufacturer Chew (James Hong) appears to live alone, and genetic engineer J. F. Sebastian (William Sanderson), who helped design the replicants, exhibits both social isolation and a typically Aspie ”special interest” in things rather than people:

PRIS: You must get lonely here, JF.

SEBASTIAN: Not really. I make friends. They’re toys. My friends are toys. I make them. It’s a hobby. I’m a genetic engineer.

Nor is there any hint of relationships for Bryant, Gaff (Edward James Olmos) or Holden (despite his injuries nobody asks about how his family are holding up.)

In fact, the only sense of any emotional bonds we see in the film is between the supposedly emotionless replicants: as we see during Deckard’s ESPER analysis of Leon’s ”precious photographs” the replicants appear to have roomed together in Leon’s apartment, and Zhora (Joanna Cassidy) appears to be working to support the others while they attempt to infiltrate the Tyrell Corporation.

It’s the treatment of empathy in both texts that has attracted the interest of Aspies though. One member of Wrong Planet posts:

Recently, I’ve been thinking about the movie Bladerunner, or more specifically, the replicants. It struck me how, as their creator, Tyrel, described them, they only have a few short years to learn how to learn emotional responses that everyone else takes for granted. They sound a great deal like us, except it takes us pretty much a lifetime. Anyone else have an opinion?

It is the psychometric test for empathy in the movie, the Voight-Kampff test which has drawn most attention as it bears many similarities to diagnostic tests used in the assessment of people with Asperger’s.

As another poster responds:

I’d have a similar opinion of the film, I actually saw the thing and the first thing that I wondered was if i’d pass the test used.

An Aspie post at aspergersbutterfly entitled ”Bladerunner, revisited” makes a similar connection:

Close friends of mine will immediately groan at this title, and may very well not even bother to read this post at all. I, in my single-minded, Asperger-ly focused way, bring everything back to Bladerunner like Terry Gross, of NPR’s Fresh Air, somehow manages to brings every conversation, with every guest, back to the HBO show, Oz. But this time, I have found out why this movie has resonated within me so much throughout the years: the empathy test that the replicants must pass. I always found myself siding with the replicant; I too would have asked the same questions, would have been confused by the ambiguity of the questions. I was smart like Roy Batty, crazy like Priss, and had a childish demeanor like that of JT. Am I a replicant? Or were replicants modeled on Aspie’s? Or perhaps its high time I reread the book, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

“I’ve already had an IQ test this year”

I want to look at a Voight-Kampff sequences in detail before a broader discussion of empathy as it not only raises the issue of empathic response but also illustrates some of the communication difficulties people with Asperger’s face.

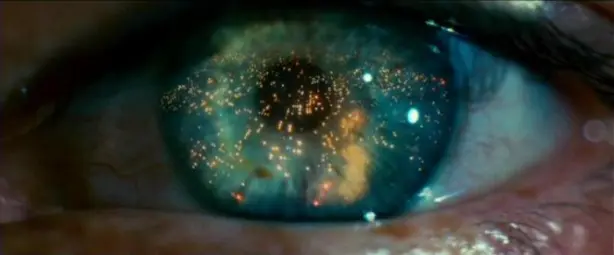

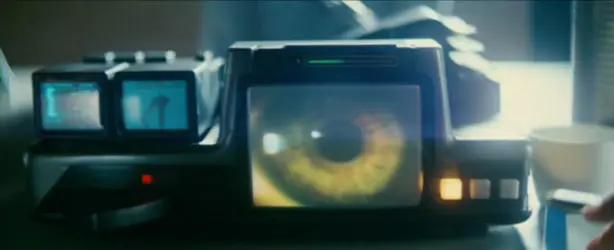

After the opening shots of the near future Los Angeles skyline we cut to an extreme close-up of the pupil of “blade runner” Dave Holden (Morgan Paull): the next few shots will cross cut between the city skyline and the eye in which it is reflected and we will slowly cut to the window of the gigantic Tyrell Corporation pyramid

The image of the eye will become a recurrent motif throughout the film.

Space

Holden is about to administer the “Voight-Kampff” empathy test to Tyrell Corporation employee Leon Kowolsky (Brion James) in order to determine, we later learn, whether Leon is human or not:

HOLDEN: Sit down.

LEON: Okay if I talk? I kinda get nervous when I take tests.

Holden doesn’t answer. He’s centering Leon’s eye on the machine.

Among the measurements the Voight-Kampff machine makes is pupil dilation.

We are only minutes into the film and we are already presented with another extreme close-up of an eye. There’s a difference between the way Holden’s eye and Leon’s are presented, however: Holden’s eye dominated the screen; we saw the entire cityscape reflected in that eye. Leon’s eye on the other hand is framed within another frame: the screen of the Voight-Kampff machine. Holden’s eye is the privileged, “objective” eye of the clinician; Leon’s eye is “subject” to the clinician’s gaze. Holden’s eye is a “seeing” eye; Leon’s is an eye which is “seen.” This is a neat illustration of the imbalance of power between the clinician, as representative of the State, and those who fall under their scrutiny.

Eye-tracking devices are, in fact, used to diagnose autism in babies. Autistic children focus much less on faces than neurotypical children. The autistic’s lack of eye contact is often taken as a sign that we lack an instinctive appreciation of it’s importance in communication – but this would not explain why we often avert our gaze; if we didn’t recognise its importance we would be indifferent to eye contact, not uncomfortable with it. This lends some support to the idea that we experience perception and emotion too intensely (the “Intense World Theory”) rather than have deficits.

The eye is a sensitive organ and much of the violence in the film is directed at the eye: when Leon attacks Deckard later in the film (“Wake up – time to die!”) he attempts to kill him with fingers directed at his eyes; Batty also kills Tyrell by forcing his thumbs into his eye sockets.

The eye is the single most vulnerable aperture in your body. Without your eyes, man, you’ve got nothing. And sticking something through someone’s eye is a very simple way of killing somebody.

—— Ridley Scott, quoted in Paul Sammon, Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner

But as well as being vulnerable to physical assault the eye is vulnerable to the gaze of those who read emotion: the eye is the “window to the soul”. At this point Leon is in the vulnerable position and does as he is told.

HOLDEN: Don’t move.

LEON: Sorry.

He tries not to move, but finally his lips can’t help a sheepish smile.

LEON: I already had I.Q. test this year. I don’t think I never had one of these.

“I already had an I.Q. test this year” is a curious statement: most of us will have had an I.Q. test as children and some of us may have had them as adults if we are applying for particular jobs or membership of an organization like Mensa but we certainly wouldn’t have one annually as this line suggests: this is an unexplained remnant from the novel in which the population are routinely tested to identify “specials” like J. R. Isadore to prevent them from having children or emigrating off-world: it’s not only the androids who are subject to legal restrictions cloaked in medical discourse in this world.

Between 25 and 70% of autistics have some form of learning disability; since the differential diagnostic criteria for HFA and Asperger’s exclude those with learning disabilities the I.Q. of those on that end of the spectrum will be higher than the non-autistic average but this is an artefact of the definition of the condition. We can presume Leon successfully met the standards set by the Tyrell Corporation otherwise he wouldn’t be working there – and in his later encounter with Deckard we will see that he is highly intelligent and philosophically inclined – yet he appears confused and distracted throughout this interview.

HOLDEN: Reaction time is a factor in this so please pay attention. Answer as quickly as you can.

Why is “reaction time… a factor” in this? Though we’ll learn that the test is a test of empathy there doesn’t seem a scientific reason for assuming that faster responses are necessarily indicative of a depth of feeling. Many aspies show a delay in processing information but this is no more an indicator they can’t process it than a delay caused by a satellite relay indicates a speaker doesn’t understand English. (My own Processing Speed Index (PSI) is clinically significantly lower than my General Ability Index.)

Leon compresses his lips and nods his big head eagerly. Holden’s voice is cold, geared to intimidate and evoke response.

LEON: Uh… sure…

Leon is uncertain of the social rules of the interview and begins by asking if it is okay to talk. He is unable to gauge when the introductions have been completed and the test has begun and interrupts Holden at several points during the interview, often taking the conversation off at tangents. His speech is hesitant, often trailing away into ellipses. These are common Aspie traits: the natural conversational turn-taking neurotypicals take for granted is almost entirely absent in this scene.

HOLDEN: One one eight seven at Hunterwasser….

LEON: Oh… that’s the hotel.

HOLDEN: What?

LEON: Where I live..

HOLDEN: Nice place?

LEON: Huh? Sure. Yeah. I guess. Is that.. part of the test?

Holden smiles a patronising smile.

HOLDEN: Warming you up, that’s all.

LEON: Oh. It’s….

HOLDEN: You’re in a desert, walking along in the sand when -.

LEON: Is this the test now?

HOLDEN Yes. You’re in a desert, walking along in the sand when all of a sudden you lookdown and see a -.

LEON: What one ?

It was a timid interruption, hardly audible.

Leon’s mumbling is also an aspie trait; difficulty in judging the appropriate pitch or volume for conversation is common.

HOLDEN: What?.

LEON: What desert?.

HOLDEN: Doesn’t make any difference what desert.. it’s completely hypothetical. that’s all.

LEON: But how come I’d be there?

HOLDEN: Maybe you’re fed up, maybe you want to be by yourself.. who knows. So you look down and see a tortoise. It’s crawling toward you…

LEON A tortoise. What’s that?

HOLDEN: Know what a turtle is?

LEON: Of course.

HOLDEN: Same thing.

LEON: I never seen a turtle.

Note that Leon focuses on the details of the hypothetical scenario rather than the ‘big picture’: What desert? Why is he there? What is a a tortoise? He takes the questions literally – again a typical AS trait. Leon seams to be deliberately pulling the interview off at a tangent; to someone unfamiliar with AS trait this could easily be seen as dissembling, a delaying tactic or an attempt at distraction.

Nevertheless even Leon becomes conscious that Holden is becoming exasperated: Asperger’s is on the Autistic Spectrum and it is a fallacy to think Aspies are entirely incapable of discerning emotion – even if it is more difficult than for neurotypicals.

He sees Holden’s patience is wearing thin.

LEON: But I understand what you mean.

HOLDEN: You reach down and flip the tortoise over on its back, Leon.

Keeping an eye on his subject, Holden notes the dials in the Voight-Kampff. One of the needles quivers slightly.

LEON: You make these questions, Mr. Holden, or they write ’em down for you?

Disregarding the question, Holden continues, picking up the pace.

HOLDEN: The tortoise lays on its back, its belly baking in the hot sun, beating its legs trying to turn itself over. But it can’t. Not without your help. But you’re not helping…

LEON: Whatya mean, I’m not helping?

HOLDEN: I mean you’re not helping! Why is that, Leon?

Holden looks hard at Leon, piercing look. Leon is flushed with anger, breathing hard, it’s a bad moment, he might erupt.

Leon is becoming angry and suspicious, a common aspie response to stress. Aspies are often as blind to our own spiralling emotions (alexithymia) as we are to others so fail to “count to ten” when provoked. Something interesting has happened to the soundtrack by this point: we hear Leon’s heart rate begin to pound. This is a switch in the scene’s perceptual point of view: where earlier the scene had privileged Holden’s point of view – demonstrated in the unequal ways in which the protagonists’ eyes were framed onscreen – we have now entered Leon’s perceptual space. At the very moment Holden’s suspicions seem to be confirmed Leon’s physiological responses tell the audience he is no mere machine.

On Channel 4′s Psychopath Night programme Professor Kevin Dutton (author of Flipnosis and The Wisdom of Psychopaths), mistakenly, I think, suggested this scene demonstrates that the replicants are psychopaths (a view shared, incidentally, by Philip K Dick); however the shift in perspective shows this not to be the case. Dutton’s own experiments indicate that psychopathy is characterised by fearlessness – the subject’s heart rate may even drop under stress – while Leon’s heartbeat shows that Leon is truly afraid. This isn’t simulated fear – it’s not for Holden’s benefit as he can’t even hear it – it’s a genuine physiological response to the probability Leon is about to be found out. Later we’ll hear that anxiety is a ever-present factor in replicant life (“Quite an experience to live in fear, isn’t it? That’s what it is to be a slave”) – just as it is for many autistics.

Suddenly Holden grins disarmingly.

HOLDEN: They’re just questions, Leon. In answer to your query, they’re written down for me. It’s a test, designed to provoke an emotional response. Shall we continue?

Leon is glaring now, the blush subsides, his anger slightly defused. Holden smiles cheerfully, very smooth. Leon nods, still frowning, suspiciously.

HOLDEN: Describe in single words, only the good things that come into your mind… about your mother.

LEON: My mother?

HOLDEN: Yeah.

LEON: Let me tell you about my mother…

Leon pulls out a gun and shoots Holden.

Leon’s attack on Holden appears unprovoked. However, we’ll later see that Blade Runners will kill replicants on sight: no arrest, no trial, just instant “retirement”. Exposure is a death sentence. Deckard will later shoot the fleeing Zhora in the back and shoot the unarmed Pris; he shoots the sixth replicant Mary as she hides in a cupboard in an earlier draft of the script. Deckard also attempts to shoot Batty in the back. In this context Leon’s actions are entirely understandable. (Perhaps he also shares my dislike of psychoanalysis)

Kevin Dutton’s interest in this scene is that it appears to demonstrate that replicants do, indeed, lack empathy but he fails to make his own distinction between “cold” and “hot” empathy (or Baron-Cohen‘s “cognitive” and “affective” empathy): the difference between the ability to read emotions and actually sharing them. I’ll look at these differences in a later chapter and we’ll see then that aspies and psychopaths are mirror images were empathy is concerned: aspies have difficulty reading emotions (“cold” or “cognitive” empathy) but care deeply (“affective” or “hot” empathy) while psychopaths – being adept at spotting easy prey as well as renowned manipulators – may excellent at reading emotions; psychopaths just don’t care about the harm they cause.

Dutton’s identification of Leon as a psychopath also fails to account for his non-verbal behaviour, his lack of eye contact, his inability to read social cues, to maintain the rhythm of conversations, his mumbling, his inability to follow the gist of Holden’s questions rather than the specifics. It doesn’t account for his later childlike behaviour or his obsessional attachment to his “precious photos”. Of all the characters in in Blade Runner, perhaps Leon hits the most autistic buttons.

This sequence doesn’t appear in the book: although Holden is referenced several times he doesn’t actually appear in the novel having been incapacitated before the book begins. A later, deleted scene in the film has Deckard visit the injured Holden who advises Deckard to sleep with Rachael – a suggestion made by the empathy-deficient bounty hunter Paul Resch in the book.

I’ll examine that in Part 2, where I explore the Neurodiverse Worlds of Philip K Dick,

Notes:

- ”Aspies” is a term coined by Liane Holliday Willey in 1999. There is some debate over whether ”people-first” terms for people with autism (”person with autism”) are preferable to simply labeling someone as an ”autistic” and I leave that to those individuals to decide for themselves; Asperger’s Syndrome, on the other hand, is named after the doctor who first identified it (Hans Asperger) and to describe myself as an ”Asperger” as if I was a relative sounds absurd (and too much like an episode of South Park). ”Person with Asperger’s” sounds too cumbersome to me, so ”Aspie” it is.

- In the Theatrical Cut Bryant says that one was killed entering the building – a continuity error left in when another replicant, Mary, who was supposed to have been injured during the break-in, was written out. The Final Cut corrects the error by having Bryant say that two were killed; nevertheless, the continuity error lead to some interesting speculation about the identity of the sixth replicant which I will come back to later.

-

Although set in the future the film deliberately evokes the style and atmosphere of the classic forties film noir, and Deckard is clearly modelled on the world weary detectives of Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett. The future Los Angeles is the noir city extended into the future:

The city in Blade Runner, with its rain-slicked Los Angeles streets, faux-forties fashions, private-eye plot and world-weary narration, derives plenty from noir. This is a dark city of mean streets, moral ambiguities and an air of irresolution. Blade Runner‘s Los Angeles exemplifies the failure of the rational city envisioned by urban planners and science fiction creators, and it also recalls, by implication, the air of masculine crisis that undergirded film noir – witness Deckard’s struggle to retain, or regain, his humanity. If the metropolis in noir was a dystopian purgatory, then in Blade Runner, with its flame-belching towers, it has become and almost literal Inferno

—— Scott Bukatman, Blade Runner (BFI Modern Classics)

There is one important difference between Philip Marlowe and Rick Deckard, however:

[T]he form of Chandler’s books reflects an initial American separation of people from each other, their need to be linked by some external force (in this case the detective) if they are ever to be fitted together as parts of the same picture puzzle. And this separation is projected out onto space itself: no matter how crowded the street in question, the various solitudes never really merge into a collective experience[;] there is always distance between them. Each dingy office is separated from the next; each room in the rooming house from the one next to it; each dwelling from the pavement beyond it. This is why the most characteristic leitmotif of Chandler’s books is the figure standing, looking out of one world, peering vaguely or attentively across into another.

—— Fredric Jameson, ”On Raymond Chandler”

Deckard never fulfils that Marlowe role of linking characters together as he is too alienated himself.

Affectlessness, then, is implicit in the film. Harrison Ford’s world weary voice-over in the Theatrical Cut perfectly embodies that lack of affect as does Sean Young‘s remarkably portrayal of Rachael Tyrell.

This lack of affect is characteristic not only of Blade Runner and the work of Philip K Dick but of postmodernism in general. Fredric Jameson, in Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism has termed this flattening the ”waning of affect”. This waning is associated with a ”whole new type of emotional ground tone”: what Jameson calls “intensities”.

Blade Runner, then, like the work J.G. Ballard or David Cronenberg, is not truly a cold or emotionless work, but, like those with Asperger’s, reflects a different ”emotional landscape” or ”a new emotional ground tone”. I’ll be returning to Jameson’s theories at the end of the essay.

References:

- Aldiss, Brian (1975) “Dick’s Maledictory Web: About and Around Martian Time-Slip” in Science Fiction Studies # 5 = Volume 2, Part 1 = March 1975

- Alvarez, Joe (2011) ”Joe Scarborough: People Like James Holmes May Be ‘Somewhere On The Autism Scale’”

- Asperger, Hans [1944] “Autistic psychopathy’ in childhood” (translated and annotated by Uta Frith, 1991, in Frith, U (1991) Autism and Asperger syndrome

- Baron-Cohen, Simon (2001) ”Theory of mind in normal development and autism” (pdf)

- (2004) The Essential Difference

- (2010) ”Empathic Civilization’: Do We Have Empathy Or Are We Just Good Rule Followers?”. Huffington Post # 3rd March 2010

- (2011) Zero-Degrees of Empathy (aka The Science of Evil: On Empathy and the Origins of Cruelty)

- (2011) ”Simon Baron-Cohen Replies to Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg” at Autism Blogs Directory

- Batson, C., Lishner, D., Cook, J., and Sawyer, S. (2005). ”Similarity and Nurturance: Two Possible Sources of Empathy for Strangers”. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 27, 15‐25.

- Bettelheim, Bruno (1959) “Joey: A ‘Mechanical Boy”. Scientific American # 200, March 1959

- Blakeman, John (2010) The Merger of Fact and Fiction: Philip K. Dick’s Portrayal of Autism in Martian Time-Slip

- Botvinick M., Jha A.P., Bylsma L.M., Fabian S.A., Solomon P.E., Prkachin K.M. (2005). “Viewing facial expressions of pain engages cortical areas involved in the direct experience of pain”. NeuroImage 25 (1): 312–319.

- Broderick, Damien (1995) Reading by Starlight: Postmodern Science Fiction(pdf)

- Scott Bukatman (1997) Blade Runner (BFI Mdern Classics)

- Buncombe, Andrew (8 January 2007). “Asperger’s syndrome: The ballad of Nikki Bacharach”. The Independent (London). Retrieved 3 May 2010.

- Cheng Y., Yang C.Y., Lin C.P., Lee P.R., Decety J. (2008). “The perception of pain in others suppresses somatosensory oscillations: a magnetoencephalography study”. NeuroImage 40 (4): 1833–1840.

- Christopher, Tommy (2011) ”Autistic Journalist Demands Joe Scarborough Retract Comments Linking Autism To Aurora Shooting”

- Chew, Kristina (2004) ”Fractioned Idiom: Poetry and the Language of Autism”

- Cohen-Rottenberg, Rachel (2011) ”Deconconstructing Autism as an Empathy Disorder: A Literature Review”

- ”Unwarranted Conclusions and the Potential for Harm: My Reply to Simon Baron-Cohen”

- ”The Empathy Issue is a Human Rights Issue”

- ”A Critique of the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test: Introduction and Part 1”

- ”A Critique of the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test: Part 2”

- ”A Critique of the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test: Part 3”

- ”A Critique of the Empathy Quotient (EQ) Test: Conclusion”

- Dennett, Daniel C. (2006) Kinds of Minds

- (2013) Intuition Pumps and Other Tools for Thinking

- Dick, Philip K. (1958) Martian Time-Slip

- (1962) The Man in the High Castle

- (1968) Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

- Dutton, Kevin () Flipnosis

- The Wisdom of Psychopaths

- Fancher, Hampton & David Peoples (1981) Blade Runner: The Shooting Script

- Fauchier, Ludovic (2013) ”Aspie, or not Aspie ? – Le petit abécédaire Asperger, chapitre 16”

- Gallese V., Goldman A.I. (1998). “Mirror neurons and the simulation theory”. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2 (12): 493–501.

- (2001). “The “Shared Manifold” hypothesis: from mirror neurons to empathy”. Journal of Consciousness Studies 8: 33–50.

- Gernsbacher, Morton Ann (2007) ”On Not Being Human”(pdf)

- & Jennifer L. Frymiare (2005) ”Does the Autistic Brain Lack Core Modules?” (pdf)

- Grandin, Temple (1986) Emergence: Labeled Autistic (1986)

- (1996) Thinking in Pictures: Other Reports from My Life with Autism

- Greenman, Jan (2007) ”My son is a monster with autism”, MailOnline, 16th Aug 2007

- Hadcroft, Will (2004) The Feeling’s Unmutual: Growing Up with Asperger Syndrome (Undiagnosed)

- Heavy, L., Phillips, W., Baron-Cohen, S. and Rutter, M. (2000) ”The Awkward Moments Test: A Naturalistic Measure of Social Understanding in Autism” (abstract)

- Hann, Michael (2013) ”Gary Numan: ‘Critics said I was wooden on stage – I think it’s true!’” Guardian, Thursday 10 October 2013

- Heinlein, Robert A (1961) Stranger in a Strange Land

- Hoopmann, Kathy (2001) Of Mice and Aliens: An Asperger Adventure (2001)

- Jacobs, Bárbara (2003) Loving Mr Spock: Understanding an Aloof Lover Could it be Aspergers Syndrome?

- Jakobson, Roman (1956) ”Two Aspects of Language and Two Types of Aphasic Disturbances” (pdf). Fundamentals of Language (1971)

- Jameson, Fredric (1983) ‘On Raymond Chandler”

- (1991) Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism

- Jeter, K.W. (1995) Blade Runner 2: The Edge of Human

- (1996) Blade Runner 3: Replicant Night

- (2000) Blade Runner 4: Eye and Talon

- Just, Marcel Adam, Vladimir L. Cherkassky, Timothy A. Keller and Nancy J. Minshew (2004) ”Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity”. Brain: A Journal of Neurology

- Lauffer, D. (2004) ”Letter to the Editor: Asperger’s, Empathy and Blade Runner”. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders . 34(5): 587-588.

- ”Linguistics 201: Language and the Brain”

- Lette, Kathy (2012) The Boy Who Fell to Earth

- Liberman, Mark (2004) ”Autism as lack of Neurological Coordination”, Language Log

- Henry Markram, Tania Rinaldi & Kamila Markram ”The Intense World Syndrome – An Alternative Hypothesis for Autism”

- McIntosh, Dean, ”Revisiting the classics: A look at Blade Runner” at I Still Find It So Hard

- Milgram, Stanley (1963). ”Behavioral Study of Obedience”. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 67 (4)

- Peña, José Ramón Alonso (2011) ”¿Tienen los replicantes de “Blade Runner” síndrome de Asperger?”

- Pinker, Steven (2002) The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature

- (2011) The Better Angels of Our Nature: A History of Violence and Humanity

- Potts, Jonathan (2004) ”Carnegie Mellon and University of Pittsburgh Scientists Discover Biological Basis for Autism” at Carngeie Press Media Relations

- Printz, Jesse J. (2011) ”Is Empathy Necessary for Morality?”. Forthcoming in P. Goldie and A. Coplan (Eds.). Empathy: Philosophical and Psychological Perspectives

- Ramachandran, Vilayanur S. and Oberman, Lindsay M. ”Broken Mirrors: A Theory of Autism” (pdf). Scientific American. October 16, 2006.

- Sacks, Oliver (1993) “An Anthropologist on Mars“, The New Yorker, 27th December, 1993

- Sammon, Paul (1996) Future Noir: The Making of Blade Runner

- Smith, Matt (no, not that Matt Smith) ”J.G. Ballard and the Death of Affect”

- Stürmer, S., Snyder, M., and Omoto, A. (2005). Prosocial Emotions and Helping: The Moderating Role of Group Membership. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 532‐546.

- Tevis, Walter (1963) The Man Who Fell to Earth

- Thompson, Stephen ”Joey the Mechanical Boy” (pdf)

- Tomasello, M, Carpenter, M, Call, J, Behne, T and Henrike Mol (2005) ”Understanding and sharing intentions: The origins of cultural cognition” (pdf) Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2004

- Tsoudis, Olga. (2002). “The Influence of Empathy in Mock Jury Criminal Cases: adding to the affect control model” (pdf). Western Criminology Review 4(1): 55‐67.

- Vernon, Mark (6 September 2010). “You have to be kind to be cruel”. Society. New Statesman.

- Westfahl, Gary (March 2006) “Homo aspergerus: Evolution Stumbles Forward” Locus Online

- Wickman, Forrest (2012) “I, Actor: Cinema’s Finest Robot Performances”. Slate. 9th June 2012

- Wing Lorna (1981). “Asperger’s syndrome: a clinical account”. Psychol Med 11 (1): 115–29.

I see me when I see the “robots” in Blade Runner.

And I’m also an “Aspie”.

And the funny thing is that I have a ~ 2 m picture of my eye on the wall since ~ 10 years without ever having watched Blade Runner before 2017 just because I wanted to have one.

I’ve always identified with the replicants in Blade Runner – but it was only during my assessment for Asperger’s that I really started thinking about the connections.

I was actually rereading Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep during my assessment.

Excellent thank you so much. I also see David from Prometheus has traits and is very interesting to watch.

Thanks. I keep meaning to do a follow up about Blade Runner 2049. Two of the cast had played Aspie like characters before: Ryan Gosling in Drive (several reviewers suggested the character is autistic) and Dave Bautista in Guardians of the Galaxy (Drax the Destroyer has great difficulty with figurative language and I read a letter in a newspaper from the mother of an autistic child who said ‘He’s just like me!’).

And you are right about David in Prometheus. I’ve got a draft of another article on sf and autism that I should really finish which includes two Davids: the other being the android boy in Speilberg’s <A.I.: Artificial Intelligence.

[…] autiste anglophone plus à fond dessus que moi qui l’a longuement analysé l’explique : https://speakertoanimals.wordpress.com/2017/03/27/do-aspies-dream-of-electric-sheep/, dans les thèmes récurrents de K Dick il y a notamment des éléments importants aussi dans nos […]